It was not always the case that Leonardo da Vinci was recognised first and foremost as the polymath ideal of the renaissance man, as for many decades after his death his fame had more to do with his artistic genius, since his paintings and murals were there on the walls of galleries and churches for all to see, whilst his notebooks lay gathering dust in an attic.

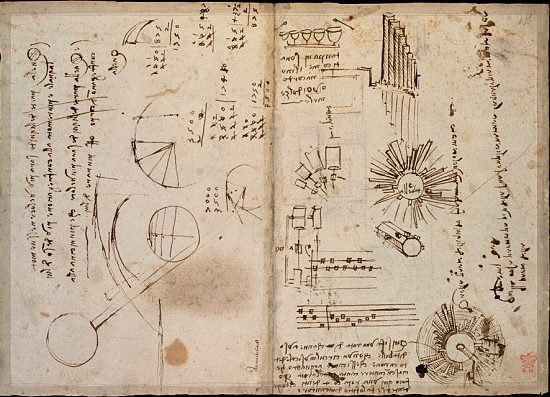

Leonardo’s notes, sketches, observations and musings are made on loose sheets of paper of differing sizes, using ‘mirror writing’ which he writes with his left hand, from right to left. For the casual observer this makes them difficult to decipher, or even makes them think he is writing in a foreign language. In addition, his spelling is sometimes inconsistent, and he uses abbreviations. When he dies, and bequeaths them to Melzi, there are over 7,000 sheets that he has not organised into any recognisable filing system.

Melzi feels the weight of responsibility and history – his first decision is to make a catalogue of what he has inherited to ensure its preservation, but this is an almost impossible task in that he is the only person who is accustomed to Leonardo’s unique writing style and can transcribe the notes more or less accurately, so help is in short supply. He then plans to organise the pages into a chronological order, since in that way the reader could follow Leonardo’s train of thought, and the development of his ideas, and how one interest might have led to another. But it is soon obvious that this will also be impossible because there are few dates and not enough other indications of timings. He wonders – how can someone who had the most amazing intellect, who could converse knowledgeably and charismatically on almost any subject, have such an unorganised method of written communication, as if the notes were only for him and not for humanity. So he concludes that the next best option is to organise by subject matter.

Knowing that Leonardo had expressed a desire, once again unfulfilled, to compile a treatise on painting in which he would pass on his learnings to other artists and make the case for painting as a science not an art, Melzi starts by bringing together all of the pages which support this objective, transcribing, making notes as he goes and compiling a large manuscript, that will become known as the Codex Urbinas1 and ends up in the Vatican Library. This alone takes many years and he is still working on it into the 1540s. His aim that in his remaining lifetime he will achieve what Leonardo did not, that is to publish his work, will not be fulfilled, although he does gather some of the separate sheets into notebooks, and manages the relatively more achievable objective of completing a number of paintings that were left unfinished at Leonardo’s death.

Francesco Melzi dies in 1570, and leaves his estate north of Milan to his son Orazio Melzi, a lawyer. But this is more than 50 years since Leonardo has died, and Orazio knows little about him or his father’s life’s work, and therefore does not understand the value of his inheritance. Thus for years, the papers lie gathering dust and unpublished in Orazio’s attic, until in 1587 a tutor in the household comes across them and takes a bundle of thirteen manuscripts, without permission, with the aim of selling them to the Medicis in Florence. The Medicis are frustratingly uninterested so, his theft now out in the open, the tutor arranges for them to be returned to Orazio, who is surprised at all the fuss and bother. He does perhaps though finally realise the public interest, and when Pompeo Leoni, an Italian-born sculptor, expresses an interest he is more than amenable to a discussion, particularly since Leoni claims to be acting on behalf of his patron Phillip II of Spain. Evidence of Leoni’s fraudulent claims will be laid bare in the next generation when his son-in-law and heir sells his inheritance – which is the largest extant collection of works by Leonardo da Vinci – to a Milanese Count who later bequeaths it to the Ambrosian Library in Milan. It would appear that Leoni only presented a small selection of documents to Phillip II, and kept the rest for himself.

Pompeo Leoni has spent most of his career in Spain and his best-known works will be the massive sculptures, in the style of bronze portraiture, of Phillip himself and his father the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and their families, that adorn their tombs in El Escorial, north west of Madrid – a royal place and monastery that is the largest renaissance building in the world. By 1590, Leoni has managed to acquire a significant part of Leonardo’s folios, including half of those that had been stolen. He too sets about re-organising what he is now the curator of and soon, as Francesco Melzi had discovered, realises the scale of the task. He decides to adhere to the principle of sorting by broad subject matter, and divides up several of the notebooks to re-arrange them into volumes, thereby further confusing their original origins. Wanting to present these volumes in a more attractive way, and to assign his own place in history, he designs a red leather binder with gold lettering that says in Italian “Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, restored by Pompeo Leoni.”

Eventually he compiles two codices: the first, which he creates by pasting the precious pages onto atlas-sized backing paper thereby making invisible anything written on the other side, is the largest, dealing mainly with science and engineering – from mathematics and astronomy, flight, architectural projects and town planning to curious inventions such as parachutes, war machines and hydraulic pumps, plus biographical records and personal notes – which will become the Codex Atlanticus, twelve volumes containing over 1,100 pages; and the second devoted to anatomical and artistic topics, will find its way after Leoni’s death in Madrid in 1608, via agents into the collection of Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel who is a wealthy art collector, then down the generations of the English nobility and royalty, surviving a civil war, into the Royal Library at Windsor Castle where it is known as the Codex Windsor. Another smaller collection of diverse pages without a particular theme, but which includes the drawings for the royal project of Romorantin, is also acquired for Thomas Arundel, which is now in the British Library. During his Italian campaign in 1796-1797, Napoleon, who is not yet Emperor, is under orders to confiscate Italian art treasures, including the Codex Atlanticus, and send them back to Paris. After the war, it is reluctantly returned to Milan but the Institut de France holds on to some other Leonardo manuscripts. A few years later, a Leonardo enthusiast studying at the Institut secretly removes a number of pages, some of which he sells on as the Flight of Birds Codex, which is handed over eventually to the Biblioteca Reale in Turin. Other pages are returned to Paris where in his absence the nefarious student has been sentenced to ten years in prison.

In the 18th century further codicies come to light, one of which is the smallest at only 36 double-sided folios focused on Leonardo’s studies of the movement of the water, geology and astronomy. This is acquired by Lord Leicester, becoming the Codex Leicester, and is in the private collection of Bill Gates, the philanthropist and founder of Microsoft.

In the 19th century John Forster, a biographer and literary critic previously mostly known for his biography of his friend Charles Dickens, bequeaths in his will three Leonardo notebooks – known as the Forster Codices – among a broader collection of manuscripts, to what will become the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In the mid-1960s, two further codices are found in the Madrid National Library, where there had for centuries been rumours and sightings. The fact that the manuscripts are found in Madrid, and in the national library, is a huge surprise, but also not a surprise given that Pompeo Leoni had lived and died in the city, and that the manuscripts had in fact been given a shelf mark in the library catalogue printed in the 19th century – Aa19 and Aa20 – but of course there were other manuscripts at those locations now. No-one thought to check whether there might have been an error in the catalogue until a French Leonardo scholar persuades the Director of Manuscripts to take another look, and in 1965 they are found at shelf marks Aa119 and Aa120. The re-discovery adds a further 350 pages to the known handwritten output of Leonardo da Vinci. These include his studies for the casting of the equestrian monument, based upon his extensive and gory research into the anatomy of horses, for the Duke of Milan in the 1490s – a major commission that was never completed beyond a life size clay model, which was used by the invading French army for target practice.

And so, from a haphazard collection of loose pages in Leonardo’s study in Clos-Lucé, each one priceless in its own right, his legacy to humanity has been thrown to the wind, some lost forever or miraculously rediscovered centuries later, to be recombined into small and large collections, disordered and without chronology, across Europe and overseas. But still much prized for all that.

Technology has now resolved all of the problems that have beset Leonardo’s notebooks over the years. All the codices are photographed, digitised, available to anyone anywhere at any time, therefore extensively analysed and studied, and searchable by any criteria you might want – not least by date.

Footnote

- Codex: Literally ‘tree trunk’ in Latin, a Codex is a collection of original ancient manuscripts combined together into a book. Traditionally, these books were of Scripture, or laws, but have been applied to collections of Leonard da Vinci’s notebooks. ↩︎