Lisa Camilla Gherardini is born in the summer of 1479 into an ancient family from Tuscany that has fallen on hard times and is living in a rented house in the centre of Florence. She grows up with olive skin, fine dark hair, long eyelashes, full eyebrows and something about her manner which, at the age of 16, attracts the attention of Francesco del Giocondo. He is fourteen years older and has been married before, but his wife has died leaving him with the sole care of a young son. His offer of marriage has pleased Lisa’s parents as he is a highly successful and wealthy man, being a Consul of the Silk Guild, one of the seven Greater Guilds in Florence. Members of his wider family are silk producers with control over its supply from ownership of the mulberry trees that provide nutrition for the silkworms, to workshops which transform the raw fibres into dyed cloth, and then to the sale of the highly sought after silks to the upper echelons of Florentine society and beyond. Along with his brother, Francesco owns two shops and rents a third, and one of his best-selling lines is a silk fabric woven with gold thread – a silk cloth of gold. The marriage, and Francesco’s career, progress well and he and his second wife have an additional son and daughter – Piero and Piera – but Piera dies at the age of two. In 1503, when Francesco decides to commission a portrait of his twenty-four-year-old wife, they have another daughter Camilla1.

By this time, Leonardo da Vinci’s reputation as a painter is well established and he has completed most of his major works including the Last Supper and Salvator Mundi. His patrons have been the most powerful men from the leading families of the independent Italian states, including the Medici, the Sforza and the Borgia – he is currently in the employ of Cesare Borgia as his military architect and engineer. Therefore Francesco achieves something of a coup in securing Leonardo’s agreement, although Leonardo’s father is a neighbour and has, in his capacity as a notary, drawn up several deeds for him, and it has to be said may have had an influence. Following the sitting, Leonardo continues to work on the small portrait, that measures only 77x53cm2, as time allows since he has received another much larger commission – to paint a mural for the council hall in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, which is to measure 17×7 metres3.

Five years go by and Leonardo leaves Florence for Milan in 1508 at the request of the French Governor, and by extension the French King Louis XII, having failed to complete either the larger or smaller commission, claiming ‘technical difficulties’ with his paints. Once he has left Florence, he abandons any attempt to deliver the portrait of Lisa Del Giocondo, and therefore never receives any payment for his work. It becomes for him a type of ‘work in progress’ on which he experiments over the years with fine layers and subtle touches with the goal of achieving the ultimate ‘sfumato’4 appearance he has in mind.

In his will Leonardo leaves his paintings, which were not individually named but known to include the Mona Lisa, to his executor Francesco Melzi, although five years later they appear to be in the possession of Andrea Salai since, when his former pupil is killed by a crossbow in a duel, they form part of his estate. By whatever method it is that they come to be in Milan, they are soon sold to a representative of François 1 and returned back to France where they are put on display at the Château of Fontainebleau. Louis XIV will then transfer them to his palace at Versailles, and after the French Revolution they become the property of the republic and are put on display in the Louvre, although Napoleon briefly borrows the Mona Lisa to adorn Joséphine’s bedroom at the Tuileries.

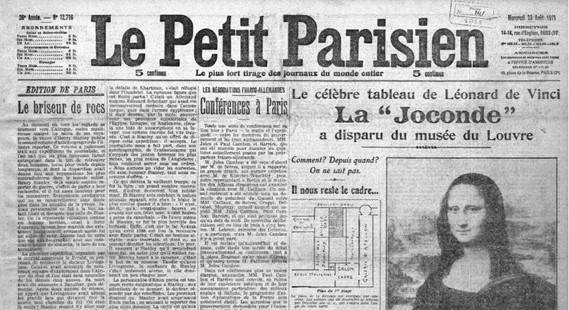

More than a hundred years later, the Mona Lisa is appreciated but not especially prized. It has come to be referred to in a number of ways: in Italy as La Gioconda; in France as La Joconde; elsewhere in the world as the Mona Lisa – Mona, or Monna as the Italians prefer, being an abbreviation of Madonna. It is somewhat unexpected therefore when in August 1911 a painter by the name of Louis Béroud arrives at the Louvre early one Monday morning, when the gallery is closed to the public and he can therefore guarantee an unimpeded view, to take inspiration from the Mona Lisa which is the subject of his own composition (retrospectively with great irony) entitled ‘Mona Lisa au Louvre’. For reasons he never explains this is a painting of the Mona Lisa and its adjacent paintings seen in situ. On this occasion, he is surprised to discover an empty space where the original usually hung, and he informs the security guards who have noticed but have assumed that the priceless portrait had been taken away to be photographed, as had happened with other paintings. The alarm is only raised some hours later when the photography studio denies all knowledge of its whereabouts.

The theft, for that is the only explanation, makes headlines in Paris, in France and abroad. It is as if the most famous woman in the world has died unexpectedly – queues form outside the Louvre that snake around the adjoining streets, and solemn crowds file past the gap on the wall to pay respects, and to leave flowers and notes. Reproductions of the Mona Lisa appear everywhere, and suddenly Leonardo’s masterpiece becomes the most recognisable painting in the world as the story gains traction but the perpetrators remain unknown. The French press offers large rewards for its return. The French authorities ramp up investigations and interview a wide cast of suspects, starting with the staff and maintenance workers, then those with an interest in art such as artists, who includes Pablo Picasso with the rationale that, as a painter of modern art which is under-represented in the Louvre, he might have stolen the classic work. It does not help his plea of innocence that he has previously, but unwittingly, bought some sculptures from an acquaintance which turn out to have been stolen from the Louvre. Even the German government (but not the more obvious Italian government) is under suspicion for a while on the flimsy basis of its aggressive stance towards the French colonies in Africa.

Two long years pass before the truth thankfully emerges, and it only does so because the culprit is not a black-market criminal, and breaks cover. Vincenzo Peruggia is an Italian glassmaker who had been employed by the Louvre (again, retrospectively with great irony) to make protective cases for its most famous works – including the Mona Lisa. Motivated by a misconception (actually not that far-fetched given what happens to Leonardo’s notebooks) that Napoleon had stolen the Mona Lisa from Italy amongst other spoils of war and that its rightful place is on the wall of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence5, he succeeds in taking the painting. He then allows enough time to pass that he assumes the story has been all but forgotten amongst all the other news, not least the sinking of the Titanic, before he outlines all this in a letter to a Florentine antiquarian to who he offers to sell the painting, signing off as ‘Leonardo’. The antiquarian informs the Director of the Uffizi, and they arrange to meet the imposter at his shop, then are taken to a nearby hotel6 where the painting is unveiled and its credentials confirmed. Peruggia, who believes he is acting on behalf of the nation of Italy and in protection of its cultural heritage, is persuaded to leave the painting for futher expert examination, and is surprised to find himself arrested the next day. In his interrogation, the details of how he stole the painting are revealed: he was employed by the Louvre and knew of its lack of alarms and how to avoid surveillance; he spent the previous night hidden in a closet; he had constructed a case in which to store the painting which, being of a sufficiently small size, he was able wrap up in the generous white smock that all employees wore; and he took a taxi back to his lodgings and hid it in a suitcase under his bed. All had not gone quite to plan though, since on his way out of the building he had found the exit door locked and in his panic had removed the doorknob which had not really helped. As luck would have it, a passing plumber had come to his assistance and opened it with a key.

Peruggia’s trial takes place in June 1914 in Florence, by which time the Mona Lisa, after being displayed for one week in the Uffizi and briefly being exhibited in Rome, has been returned to Paris in a first-class train carriage. Uncomfortably for the police, it comes to light that not only has Peruggia been interviewed twice and discounted, but that he has had contact with the law on two previous occasions – the first time for attempting to rob a prostitute, and the second for pulling a gun in a fight. He receives a relatively lenient sentence of six months in prison, partly due to the conclusion by the court that he is suffering from a mental illness. Despite this, after his release Peruggia becomes a national hero for his patriotism, and goes on to serve in the Italian Army in World War I.

During the next war, Mona Lisa is on the move again, being evacuated from the Louvre during the year before the start of hostilities for fear of bombing. Packed in a crate marked MNLP No.0 (standing for Musée National du Louvre Peintures), it is transported around France with other valuable paintings, in response to military failures and successes, spending time in Normandy, then in the Châteaux at Amboise and Chambord. In 1940 when northern France is occupied, the Mona Lisa is hidden in a Cistercian Abbey just south of Assier for the summer; however with the arrival of winter and humidity, it is taken to the Lot region, to the north of Toulouse, where it is kept in the renaissance Château de Montal, with its legend of the tragic death of Rose de Montal who threw herself from her bedroom window, and the Ingres Museum in Montauban. In all there will be at least ten hiding places before the Mona Lisa returns to Paris in the summer of 1945.

Peacetime does not prevent the Mona Lisa from being attacked. In the 1950s, acid is thrown at the painting and in a separate incident, a rock is used, which breaks the glass and slightly damages her left elbow. Following these incidents, bullet-proof glass is installed.

The Mona Lisa leaves France on only a couple of occasions after that: to the USA in the 1963; and to Moscow and Tokyo in 1974. For the trip to America, Charles de Gaulle agrees to a request by US First Lady, and Francophile, Jackie Kennedy, for the painting to but put on temporary display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and the Met Museum, in New York City. He may, or may not, have been persuaded by President John F Kennedy’s assertion, repeated in a speech just a month before his assassination, that the Kennedy’s can trace their ancestry back to medieval Italy, and specifically to Mona Lisa’s original family, along his mother’s family tree. The Fitzgeralds have a family story as to why they had always referred to themselves as the “Geraldines”, which was said to be the result of an ancestral link to a member of the Gherardini family who had left Florence early in the 11th century, and whose descendants had joined the Norman invasion of England, been gifted lands in Ireland, and much later, as the Fitzgeralds, had emigrated to America.

Footnotes

- Mona Lisa’s Children: Mona Lisa will give birth to six children. Piero lives until the age of 73; Piera dies aged 2; Camilla becomes a nun aged 12, and dies at 19; Marietta born in 1500 also becomes a nun and lives until the age of 79; Andrea, a son born in 1502 dies aged 22; Giocondo born in 1507 dies a year later. Lisa del Giocondo dies aged 63 in 1542, four years after her husband. ↩︎

- 77x53cm: 30×21 inches, i.e. 2 and a half feet in length ↩︎

- 17x7m: 56×23 feet ↩︎

- Sfumato: The sfumato technique of painting avoids bold or harsh outlines, and achieves a delicate, smoky (sfumato derives from the Italian fumare – to smoke) effect by blurring and blending layers. X ray analysis of the Mona Lisa by Pascal Cotte in 2007 reveals up to 30 fine layers in some places. ↩︎

- Cultural Heritage: The belief that the Mona Lisa belongs in Italy is a persistent one. Italian government culture and heritage departments continue to appeal to their French counterparts for the return of the Mona Lisa to its ‘home city’ of Florence, backed by hundreds of thousands of signatures from campaigners. ↩︎

- Hotel La Gioconda: The Hotel Tripoli-Italia, where Peruggia revealed the Mona Lisa to the Director of the Uffizi Gallery, was afterwards renamed Hotel La Gioconda. There is a commemorative plaque outside Room 20 where Peruggia stayed. ↩︎