A Judgement of Sir Ranulphe Crewe

This is a shorter version edited from “Blue Blood Like Blue Ink” (see About section).

Discountenanced

I thought I had found a brief memoir, some reminiscences of his life, but the few pages of notes at the back of great-grandfather’s tattered photograph album turned out to be a summary of the research he had been carrying out into the history of his aristocratic ancestors, the Crewe family. It was evident that he had dictated them and that his eldest daughter had typed them up. The purpose was, it seemed to me, to discover where all the titles and money had gone, as he was a well-off businessman but did not possess a stately home and estates or even, by the time he died, the Crewe name itself. On the final page, his daughter had tried to create a family tree but had become frustrated by the difficulty of drawing lines using the typewriter, so had resorted to a blue pen to make the connections. I remember thinking that this was more appropriate, as it looked like blue blood.

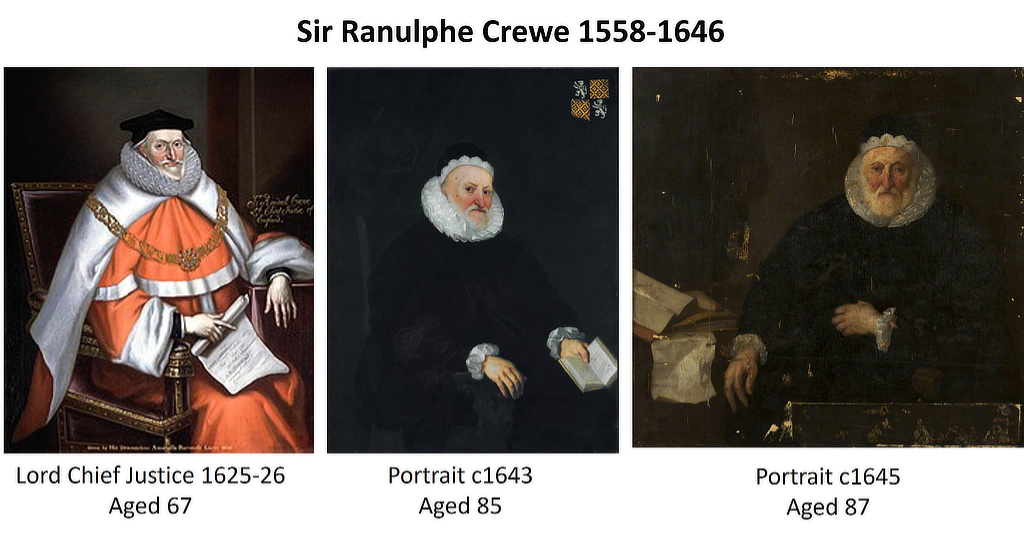

The central character from whom all lines emanated was Sir Ranulphe Crewe1, the founder of the Crewe dynasty. He was the epitome of the self-made man, who rose from relatively humble beginnings in Cheshire in the mid-sixteenth century to become Lord Chief Justice of the Kings Bench, the most powerful judge in the country, under not one, but two Kings: James I and Charles I. Not forgetting his roots – in fact he was obsessed by his genealogy – he built one of the largest houses in the North of England of the time, Crewe Hall, as well as maintaining a comfortable ‘town house’ in Westminster. I did my own brief scan of his achievements. He had his own Wikipedia page and an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and seemed to be best remembered for a quote about lost noble family names, but I noted that he received almost unanimously favourable testimonials from his peers and historians of the period. On his character: “…he did not seek to obtain the applause of the world; he was a modest man… contented with the approbation of his own conscience.” On his legal career: “…his legal honesty and political consistency raised him high in the estimation of all public-spirited men.” As Lord Chief Justice: “…there was never a more laudable appointment… he had patience in hearing, evenness of temper and kindness of heart.” There was just one flaw. In the summer of 1616, Sir Ranulphe Crewe was one of two senior judges who hanged six innocent women as witches, a decision for which they were censured by James I, a revelation in itself as the King had confirmed, and indeed broadened the scope, of the death penalty in his Witchcraft Act of 1604.

I could have left it at that. After four hundred years of praise, why not leave this unedifying stone unturned? But then I discovered that there still existed twenty-four pages of vellum manuscripts from the trial of the Bewitchment of John Smith (a Child) 1616 in the Lincoln Archives, and that a local historian had made a transcript.2

Read more