Leonardo da Vinci and his assistants along with the train of mules carrying his personal belongings, furniture and paintings, one of which is the Mona Lisa which he is still working on, arrive in the Château de Clos-Lucé in the summer of 1516. It has been a long and arduous journey of a thousand miles which has included hurriedly crossing the Alps before the winter set in.

This is the first time in his long life – he is sixty four but with his long grey hair and beard looks much older – that he has left his native Italy. His previous patrons have provided him with work in the various city states of Italy, initially in Florence, then Milan and most recently in Rome where he was lodged in the Belvedere Villa, a recent addition to the Vatican with sweeping views across the city. Here he was employed by Pope Leo X, but found himself struggling to compete with the fame of the younger Michelangelo, riding a wave of admiration following the completion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling after four years of effort.

It was as part of the Pope’s entourage that set out in late 1515 to meet François 1 in Bologna to discuss peace terms, following his anointing as Duke of Milan, that Leonardo met his final patron. In advance of the meeting, the Pope had commissioned an invention from Leonardo that would amuse the young king of France and could be given as a gift. This turned out to be a mechanical lion, two meters high and three meters long and made of wood, that was able to move by way of a single spring and cogs that controlled its motions. It could take a few steps forward, move its tail and sit up on its hind legs. Having done this, a compartment would open up in its chest and a bouquet of lilies would be presented. Lilies were part of the Medici coat of arms, and the Pope had been Giovanni de Medici prior to being anointed as the last ‘non-priest’ to become leader of the Catholic church.

François was already an admirer of Leonardo through his knowledge and admiration for the Italian renaissance, and this must have been the ideal opportunity to offer him security in his old age, as the uncertainties due to the Italian wars continued. Despite his fame, Leonardo is illegitimate and not a rich man by birth so he relies on commissions, many of which he has not completed due to his unstoppable curiosity in everything around him. The title they agree on is “First Painter, Engineer and Architect to the King” and the job comes with a grace and favour home near to the French Court’s summer residence in Amboise, and a decent pension.

Clos-Lucé is a compact red brick Château close enough to the Château of Amboise to be attached to it by an underground tunnel. There is extensive parkland and a vineyard to wander in. It has an emotional meaning to François and Marguerite as this was where they had spent their childhood. Leonardo sets up his study in one of the rooms on the ground floor which has high ceilings and large windows so that it is full of natural daylight, and he arranges within it his precious belongings: his notebooks on a simple desk; his three paintings – the Mona Lisa, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, and St John the Baptist – on easels; and his books and collections from a lifetime of varied interests, from anatomy to zoology, which are placed on shelves around the room. He also finds the right spots to place his prized cabinets and chests, which are fine examples of Italian design and workmanship.

Leonardo’s later life settles into its routine. Although he is mostly free to spend his time on what interests him most, he feels obliged to support the court in preparation for its key events. He designs some of the decorative elements for the celebrations of the christening of the Dauphin (also called François) at the Château of Amboise where the Pope is the Godfather (although he sends his nephew Lorenzo de Medici1 in his place) and Marguerite d’Angoulême is the godmother. The main courtyard is covered against inclement weather by a very large and luxurious golden tent, which could possibly be re-purposed for later use. He also reproduces, for a royal banquet, one of his greatest successes – a re-creation of parts of the operetta La Festa del Paradiso, which he first designed in 1490, in which the performers are dressed as planets under a ‘sky’ made of pale blue cloth with embroidered gold stars. As ever, the centrepiece is a mechanical contraption – an enormous wooden orb that opens up to reveal paradise.

As well as a workplace, Leonardo’s study becomes a living museum which he delights in showing guests around. Although he suffers a stroke which affects the mobility of his right side – fortunately he is left-handed – he is well enough to be visited by Cardinal Luigi d’Aragona from Naples, who is making a tour of Europe accompanied by a large retinue including his private secretary, De Beatis2, charged with recording the travels for posterity in his diary. They receive the full tour including an exhibition of the paintings and an explanation of the techniques Leonardo has developed, as well as sight of the contents of his notebooks in which he has sketched the internal details of bodies drawn from his experience of, he is recorded as admitting, the dissection of more than thirty bodies of both sexes and of all ages. Lunch was prepared by Mathurine, the cook at Clos-Lucé, who had been forced to develop a whole new menu since Leonardo was a vegetarian – his belief being that this was a healthier diet, especially as you aged.

Leonardo’s most frequent visitor by far is François I, and the two men are like father and son, or rather teacher and pupil. François, well-educated and innately curious himself, is in awe of the sheer scope of Leonardo’s mind – he is a living encyclopaedia who, despite a rudimentary education and not attending university, can converse on an unparalleled range of subjects such as painting, sculpture, architecture, science, mathematics, engineering, geology, botany, astronomy, anatomy, music, literature, history, and cartography – and François uses him as the engine of his search for knowledge. This is fortuitous since François is attempting to quickly build a reputation, both intellectually by bringing and translating renaissance ideas from Italy to France, and physically by a vast programme of building work. He already has plans for the renovation of both the Château d’Amboise and the Château de Blois. Later he will remodel the Château de Fontainebleau and its gardens into an Italian renaissance masterpiece, and then he will convert the medieval fortress of the Louvre into a French renaissance-style primary royal residence in Paris, where he plans to eventually house his art collection. But first he wants to create something new and unparalleled – a state-of-the-art capital city for France – and Leonardo is the ideal city planner.

The site François chooses is at Romorantin, a pretty village with a château, medieval churches, half-timbered houses, farms and mills on the river Sauldre, a tributary of the Loire, some 60km east of Amboise and 200km south of Paris. He says by way of explanation to Leonardo, who is invited along on a reconnaissance mission, that this is where he grew up in a minor royal palace belonging to his father’s family, the Counts of Angoulême. He forgets to mention that the name Romorantin means marshland in old French, and that insects blight the landscape in summer.

This is not the first time that Leonardo has thought deeply about how a modern city should be constructed. It had become evident during the many plagues that struck Europe in the middle-ages, that the design of medieval towns was unhealthy. The houses were clustered too closely together, overhanging the narrow streets and depriving them of air and light, and the sanitation habits of the inhabitants, plus living in close quarters with animals, led to the easy spread of disease. So, following a particularly deadly outbreak of plague in Lombardy, and taking inspiration from similar attempts at urban planning in Pienza which were influenced by the rediscovery of classical architectural principles, Leonardo had been commissioned to come up with design for a modern, healthy Milan.

His drawings from that first attempt reveal that that the city was to be built on two levels, and that, unrealistically but in keeping with a utopian vision, there were to be no city walls for defence. The upper level was mainly pedestrianised for the more affluent citizens to walk unhindered along its wide streets, squares and open spaces between the public and civic buildings. These had staircases on the outside to maximise internal space and on the exterior walls he had also placed fresh air vents. The lower level was reserved for the supporting infrastructure – a canal system for transport and water management for sewage, plus shops and trades – and by inference the lodgings of the working people and animals associated with these services.

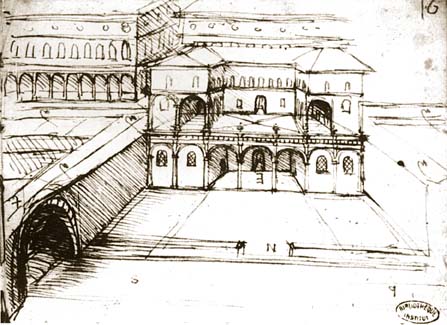

In Romorantin, Leonardo and his friend and apprentice, the artist and nobleman Count Franceso Melzi3, remain on site for several weeks and are lodged in the Chancellery; Melzi takes measurements so that Leonardo’s preliminary sketches are to scale. The cityscape that evolves is, not unsurprisingly, neo-classical in style with Greek influences apparent in the many public spaces, and myriad of fountains. As with the ideal Milan, and Leonardo’s persistent fascination with fluid dynamics, water plays a core role: rivers are to be diverted and raised so that they flow downwards to Romorantin, at a pressure high enough to power water mills; canals will be created to facilitate transport flow around the city and for the collection and disposal of waste in underground channels; a complex system for cooling and heating is proposed, consisting of a water tower and reservoir – of cold water in the summer and heated water in the winter – over which air will be forced that will be used to cool or heat both civic buildings and private houses. The same system will also provide hot and cold running water.

François can hardly contain himself when Leonardo, after many enquiries and less than subtle regal hints, feels in a position to share his preliminary urban plans. The twin palaces – one for the king and one for his mother on either side of the river – together with the buildings that house the state departments and the mansions for the members of court, are glorious examples of the new Italian renaissance style. Moreover, despite reviving some of his previous ideas which anyway he had not shared with François, Leonardo has envisaged some innovations specifically for Romorantin, including doors that automatically open via a clever system of pulleys when pressure is applied on the floor, and an internal communication system based on the sound of a voice being carried via copper pipes.

Leonardo skips quickly over the one glaring issue that his designs will lead to – the razing of the entire existing village of Romorantin and some of the surrounding towns to make way for the ‘new’ capital of France. François, in his passion for Leonardo and his ideas, is willing to separate means and ends, but decides that there is no advantage to be gained from relating this to his mother just yet. He does, though, immediately make money available for the first stages of the river diversion and drainage.

It will turn out that Leonardo’s plans are not only well ahead of their time and budget, but more inescapably, of medical advances. Malaria caused by a particularly hot summer will run rife through Romorantin, causing deaths on a scale to make François change his mind. The final decision not to create his capital from his childhood village, will not be taken until Leonardo has died, but already François’s time and energy is being re-focused more towards rebuilding the Château at Chambord. Romorantin will be yet another of Leonard da Vinci’s designs that is never realised.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Remains

After his stroke, Leonardo’s health declines. Perhaps as a manifestation of his swirling and confused feelings towards his demise, he pours out his thoughts into his notebooks in a series of drawings of water – not the serene canals of his unbuilt ideal cities, but of floods and storms.

In April 1519, aware that he is dying, Leonardo da Vinci sends for a priest to make his confession and to receive the Holy Sacrament, then he draws up his will in the presence of a notary, and succumbs barely a week later. Melzi is the executor and principal heir, and is bequeathed Leonardo’s personal possessions including his notebooks and paintings. His servant Batista di Villanis receives half of the vineyard4 that Leonardo owns in Milan, with the other half left to his former pupil and long-term muse, Andrea Salaì, who was the son of a tenant of the vineyard and who had remained living there in a house he had built himself. He does not forget his cook Mathurine to whom he leaves a black coat “of good cloth” with a fur trim. His half-brothers in Italy receive land.

He does not ask to be repatriated to the family tomb in Florence, but instead to be buried at the church of St. Florentin at the base of the Château of Amboise where the casket, having in accordance with his will been followed by sixty beggars, is placed near the altar whilst the high mass is celebrated. In hindsight, this was not a good decision. During the French Wars of Religion, a plot by the Huguenots5 to kidnap the king is discovered in Amboise in 1560, after which more than 1,000 protestants are executed. As revenge, protestants ransack Catholic churches and St. Florentin is looted, the graves inside desecrated, and the building itself is vandalised. Then, following the revolution, the Château of Amboise is badly damaged and the ruins of St Florentin are fully demolished, with its stones eventually being used in the restoration of the Château above it. Only in the middle of the nineteenth century are excavations made on the site, and some bones are discovered which may, or may not, be those of Leonardo da Vinci. These remains are transferred to the gothic chapel of Saint-Hubert which forms part of the castle walls, and will become his final resting place, covered by a simple cream marble slab.

Footnotes

- Lorenzo de Medici: Lorenzo de Medici is the ruler of Florence, and his daughter Catherine de Medici will end up marrying the Dauphin’s younger brother Henry and becoming Queen of France. Niccolò Machiavelli will dedicate his political treatise ‘The Prince’ to him in which among other advice he proposes that rulers are justified in using immoral means to ensure their victory and survival. ↩︎

- De Beatis: In his diary notes of the discussions between Cardinal Luigi d’Aragona and Leonardo da Vinci, de Beatis records Leonardo saying that the painting of the enigmatic woman he has in his study was commissioned by Giuliano dei Medici and is of his lover, who he does not name. ↩︎

- Count Francesco Melzi: History has provided a very precise evaluation of the level of genius of Melzi (40%) – accounts from the French court reveal that he was paid 400 gold coins a year in comparison to the 1,000 gold coins paid to Leonardo da Vinci. ↩︎

- Leonardo’s vineyard: The vineyard had been a present from the same Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan to whom Leonardo had sent his resume and who had later commissioned the painting of The Last Supper. It had ironically been confiscated by the French under François 1 after the victory at Marignano, and only returned to him when he had moved to France. ↩︎

- Huguenots: The name given to French protestants, first applied after the Amboise Plot of 1560; it has unclear origins although a contemporary source relates it to spirits in purgatory which only went out at night (known as le Roy Huguet in the Loire region) as did the protestants who could only meet in cover of darkness. ↩︎