Back to Early Modern Elmbridge

The Seven Day Civil War in Surrey – 12th-19th November 1642: A True Account from Letters, Pamphlets and Newsbooks

Dilemma

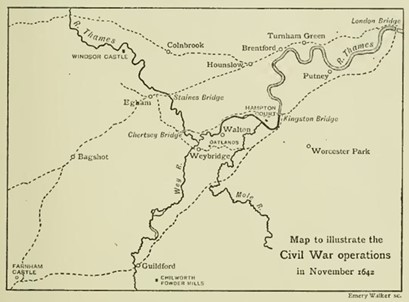

The first signs that the war was close at hand came early on the afternoon of Saturday 12th November 1642, when many people heard a series of cracking sounds that continued sporadically over the course of a couple of hours. Then, the next morning, there were reports of distant rumbles, like a giant’s muffled footsteps, followed by a huge explosion. In normal times, those living along the Thames west of London would have blamed the weather and looked for approaching dark clouds, but now they worried that, depending on the outcome of the battle being fought close by, they were soon going to find themselves caught up in the conflict between the king’s army that was marching purposefully towards the capital, and the parliamentarians trying to stop them at any cost.

News had been coming in since late summer from citizens fleeing the capital, that Londoners were preparing for an attack by the royalists, who would approach either north of the river through Middlesex, or south via Kingston Bridge and up through Putney. The ‘trained bands’ of soldiers, who were local militias of reservists called upon in times of need, had been repairing and reinforcing the city walls, and shops and businesses had been closed so that everyone, including women and children, could help by carrying baskets of earth for the ramparts, and gathering materials for the barricades. On the busier thoroughfares, great iron chains had been hung to stop the cavaliers in their tracks, and cannons were put in place beside which the gunners kept a lit flame at the ready.

London had split quickly along partisan lines. At first there were just angry words and accusations, and the adoption of symbols — royal supporters began wearing rose-coloured bands on their hats — but once news that the king had declared war was known, parliament stepped in. The Tower of London and its military resources were seized, and a Committee of Safety was established to take control of the trained bands away from the Lord Mayor and the Aldermen, who by nature and tradition supported the king. A recruitment drive was begun amongst the merchants, craftworkers and apprentices, and a further order was made to raise new troops from the county militias in the Southeast. The challenge was whether all these raw recruits could be assembled, organised and trained before the king’s army arrived.

Then came the clampdown. Anyone suspected of being a royalist ‘malignant’, or refusing to pay the levy that had been introduced to pay for the defences, was stopped and searched in the street to look for weapons, and had their homes raided and horses confiscated. Lookouts scoured the river for boats full of enemy soldiers. Roman Catholics, always thought to harbour royalist sympathies, were given twelve hours to leave London, and were told not to come within twenty miles of the capital again, or risk imprisonment. And so, a steady stream of refugees headed out towards the surrounding counties.

It was no surprise that there was a great deal of support for parliament in the city where it sat, particularly amongst the working population of merchants, craftworkers and commoners, but further afield the situation was not so clear cut. Despite twelve out of the fourteen MPs for Surrey remaining in the House of Commons whilst only two colleagues left to join the king at his new court in Oxford, the ordinary people — especially those living in proximity to the royal palaces who supplied goods, services and staff — had a dilemma. It was not so much about which side to choose, but how to avoid choosing, or at least how to prevent your allegiance becoming public knowledge until it was clear which way the wind was blowing. Even when the fighting had started at the end of October, and husbands and sons were called up1 to join the defence of the capital, those left behind agreed that it was common sense to keep your head down, or to maintain a degree of impartiality. In Shepperton, the parson, a Mr Hughes, was reported by several witnesses to have made remarks against both the Parliament: “If I were King, I would take the Tower, and beat down the city about the inhabitants’ ears!”; and the King: “I know that the King would venture his crown upon the papists’ heads!”. For the anti-parliamentary comments, reported in the Commons, Mr Hughes was jailed in the New Prison in Middlesex, to remain there at the pleasure of the House.

What was also preventing many Surrey residents from declaring for parliament were the rumours of the atrocities being committed by the king’s royal cavaliers, that had appeared in pamphlets and newsbooks, and been bellowed to the illiterate from the pulpits. At the back of their minds was the thought that, if the king’s army did descend on their towns and villages on its way to London, surely they would be spared the horrors if they were known to be loyal subjects?

Battle and Stand-off

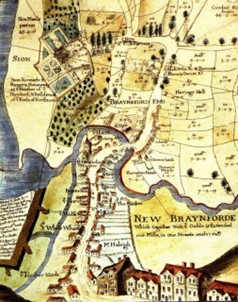

The battle that had been heard for miles around took place in Brentford on Saturday 12th November 1642, and was not fought in open countryside, but down the main street amongst the houses and gardens from where many of the residents had fled, but where others, worried about their property and possessions, cowered in fear. The town was being defended by a relatively small group of parliamentary soldiers, who despite firing volleys of musket balls from behind makeshift barricades, were overrun within a few hours by the larger royalist forces, and forced to flee towards the Thames. There, pursued by the king’s cavalry, several jumped into the river and were drowned, and the remainder were taken prisoner.

That evening, in a victory celebration, Brentford was ransacked. A tract was published shortly afterwards in London, entitled “A True and Perfect Relation of the Barbarous and Cruel Passages of the King’s Army at Old Brainford2” that described the events.

First, the soldiers drank beer and wine in the inns of the town, and when they were full, they destroyed any remaining casks and let the contents run out “in some cellars as deep as to the mid leg”. Then they plundered the inhabitants, taking “their money, linens, woollens, bedding, wearing apparel, horses, sows, swine, hens, etc. and all manner of victuals. Also, pewter, brass, iron pots, and kettles, and all manner of grocery, chandlery, and apothecary wares. Nay such was their barbarous carriage, that many of the featherbeds which they could not bear away, they did cut them in pieces, and scattered the feathers abroad in the fields and streets.” What they could not carry away, was broken or defaced: bedsteads; furniture; the doors of the houses.

Having deprived them of their possessions, the cavalry then turned their attention to the townspeople, and “they did set drawn swords and pistols cocked to mens and womens breasts, threatening them with death, if they brought not out all their money; and threatening others to cut off their noses, and pull out their eyes.”

Those suspected of being parliamentary soldiers were taken prisoner, “calling them parliament dogs, round-headed rogues… and they did put them into a pound, and there tied and pinioned them together, where they so stood for many hours, some of them they stripped to their shirts, others to their breeches, most without stockings or shoes, and in that condition removed them to the slaughter-house, where they lay all night, it being a most nasty and noisome place.”

There was a small attempt to distance this terrible account from the king: “It appears by these prodigious acts of rapine3, destruction and tyranny, that these men delight in cruelty…not for such as endeavour the defence of the King, but the ruin of the kingdom; and not as enemies of some kind of men, but as the common enemies of mankind.”

The end result was an indication of what the royalists, but especially the cavaliers, would do to any and every town or village they encountered: to leave the population — the men, their wives and children; the old and the crippled — in such extreme poverty, that they would be reduced to begging from that day forward.

The royalists had gained the upper hand, and it was feared that being only ten miles distant, they would arrive at the gates of London the next day. In the city, a desperate call went out, supported by drummers in the streets, for more volunteers to protect the main route, and preachers were asked to urge their congregations to send out the meals they were preparing for Sunday dinner to feed their brave compatriots, and so on Saturday night a steady stream of men poured out towards Turnham Green where the parliamentary army had gathered, followed by a train of a hundred wagons loaded with supplies.

On Sunday morning, the 13th of November 1642, a separate group of parliamentary reinforcements with supplies of weapons and gunpowder arrived from London in a small fleet of barges. A gentleman in his majesty’s army wrote to a friend in London that the king had attended a service and sermon before the break of day, and then about half past eight an alarm was raised when twelve ‘lighters’ or flat-bottomed barges, full of soldiers, tried to land at Syon House but were beaten back by canon fire, and one boat “in which half their ammunition lay, being 22 barrels of gunpowder, immediately took fire” and a huge explosion erupted. Several other boats were sunk, and the rest scuttled.

In the afternoon, the two sides met again, but this time on open ground at Turnham Green, where it was soon obvious to all that the situation had changed overnight. More parliamentary troops had arrived, and the call for volunteers had been a great success, so that the royalists were now significantly outnumbered. The king appeared unsure what to do, faced with a larger enemy that looked relatively fresh and well fed, whilst his men were suffering from a combination of the fighting of the day before, a premature victory celebration in the inns of Brentford and, for most, a freezing night out in the open. It was a stalemate and the armies continued to face each other for many hours, apart from some minor ‘flurting out’ or feints by the royal cavalry, trying to lure inexperienced, untrained volunteers forward to break ranks.

By late afternoon, it was growing dark, so little by little, the royal forces withdrew.

Propaganda

News of the Battle of Brentford travelled surprisingly quickly, as there was an established network of outlets for printing and publishing the many sources of information flooding in. Firstly, there were the details picked up by spies that were endemic in each camp. One such was a Mr Blake, who had become the secretary and ‘privy chamberlain’ to Prince Rupert of the Rhine, commander of the king’s cavaliers, but was providing intelligence to parliament (and thence via leaks to the printing presses) for a payment of fifty pounds per week. Unfortunately, his notes were found amongst the papers of a captured parliamentary soldier, so he was executed and unable to spend his riches.

Secondly, there were ‘journalists’ disguised as merchants. Two such men were discovered inside the cavalier’s camp in Egham on the evening prior to the Battle of Brentford, and were detained for further questioning, but managed to escape the next day during the confusion surrounding the fighting. By the end of that same day, their account was already prepared and the journal “A True Relation of two Merchants of London who were Taken Prisoners by the Cavaliers” was published on Monday. It would have been sooner, except that the printers had observed the Lord’s Day. One of their revelations was that Prince Rupert went to bed fully dressed, which they presumed was because he had vowed “never to undress or shift himself until he had reseated King Charles at Whitehall”. Another was that they had watched the king and Prince Rupert in discussion on Hounslow Heath on the morning of the battle, where the prince “took off his scarlet coat, which was very rich, and gave it to his man, and buckled on his arms, and put a grey coat over it, that he might not be discovered”, and that “he talked long with the King, and often in his communication with his Majesty, he scratched his head and tore his hair, as if he had been in some grave discontent”.

Next, several of the participants, commanders and soldiers both, were sending letters to friends and family, who were happy to pass on interesting details, and keeping diaries for posterity. After that were the eye-witness observations of the spectators who rode on horseback behind the soldiers, and assembled on a nearby vantage point to watch the action unfold. Whilst accounts that relied on hearsay could be biased, at least these latter were relatively unfiltered: one ‘Gentleman’ stated “You may confidently believe this narration; for you receive it not from my ear, but from my eye”.

All of these words — the secret notes, the journals, the letters, the observations —were back in London within a few hours, being spread in and around St Paul’s Cathedral and its churchyard, which was, as far back as living memory went, the marketplace for news, rumour and gossip, and where the booksellers were clustered. There was, therefore, a steady output of polemical pamphlets and tracts, but the growing demand was for daily ‘newsbooks’4 which contained the more outrageous stories that would incite an exhilarating terror in citizens already subject to the fear of God. Those who could not read listened instead to the sermons of the myriad of preachers with similar stories.

It soon became difficult to separate fact from fiction, and sometimes even the ‘facts’ had an unfortunate side effect. A publication entitled in part “A True Relation of the Remarkable Passages that have Happened since Saturday” reported the death of some soldiers whose wives “hearing of it, did forthwith put themselves into mourning habit”. But the intelligence was mistaken and one of them “was so overcome at the sight of his return… that she began now to feel a nearer violence from her own joy, and fainting away in his arms, had almost made him a widower, whose widow she supposed she had been”.

Publishers in London were restricted to news that favoured the parliamentarian cause, but the focus of the propaganda was not King Charles, as there were still some delicate peace negotiations going on in the background, but his nephew Prince Rupert and the cavaliers under his command. Rupert was a portrayed as a foreigner, leading a group of Catholic sympathisers who had a particular hatred for London and its wealth, and who, after ravishing its women, were going to burn it to the ground.

By contrast, to many in the shires far beyond the capital, the cavaliers were the epitome of the glory of warfare: men of gentle blood and noble bearing, youthful and long-haired, blessed with the courtier’s wit and the warrior’s swagger, and furnished in armour from their ancestral halls. They were always out front — the advanced guard —seeking out the enemy positions, harrying and skirmishing, and garrisoned in well-furnished lodgings apart from the mass of the army. Only once they had established a position, did they send out a call for the infantry to advance, with trumpets and drums, followed by the artillery. The king travelled with the foot soldiers, accompanied by his privy council, secretaries and a train of heralds. However, his perennial problem of lack of funds, which had been one of the underlying causes of his problems with parliament, meant that he was not in a position to pay his army, or to provide a stable supply of provisions. For this reason, the royalists relied almost entirely on pillaging the surrounding areas of wherever they happened to be, and it was the job of the cavaliers to undertake it, which was where the romance stopped and the anti-royalist press backlash began.

Accounts of the behaviour of the cavaliers was becoming so lurid, particularly after Brentford, that parliament did attempt to carry out some fact-checking, asking for a report to be presented and then sending out a delegation to interview some of the inhabitants to verify the conclusions, which did corroborate the findings of huge losses, estimated at four thousand pounds5. A report was prepared called ‘The Mischiefs they do by Plundering’ and sent to the commander of the parliamentary forces, Robert Devereux, the 3rd Earl of Essex6.

Pillaging and Plundering

On Monday 14th November 1642, King Charles I arrived in Weybridge at the head of a section of his foot soldiers who were leading the prisoners captured at Brentford “who numbered between four to five hundred, and had been dragged in ropes over Hounslow Heath, towards Oatlands, divers of them bare foot and bare leg, over furze7 and thistles, till their feet and legs did bleed”.

When the royal army left Turnham Green at dusk the previous day, the king had decided to go to his palace at Oatlands to consider his options. Coming first to Kingston bridge, and finding it defended by the townspeople (since the parliamentary garrison that had occupied it had left to bolster the forces at Turnham Green), the king had to plead to be let through, and finally prevailed after promising upon his regal word that no harm or hostile act would be done by his army, a promise that would not be kept by his troops once he had moved on. He left the larger part of his infantry and artillery to find billets amongst the abandoned or requisitioned houses and outbuildings, then continued towards Oatlands. Prince Rupert and the cavaliers went in front, headed for Walton-on-Thames8.

The next day, Rupert came before the prisoners “in that naked and starved condition at Oatlands” and threatened to hang them all if they not agree to renounce their puritan ways and take up arms for the royalists, but on being silenced by disbelieving jeers, he sent for a blacksmith who, he told the watching rabble, would burn the cheeks of those refusing to serve the king with hot irons. Whereupon most changed their minds, but around a hundred and fifty or so “being almost all of the red regiment of Colonel Holles’s9 soldiers, tendered their persons to be stigmatized”. This resolve so affected the prince that he released all of the prisoners, on the condition that they swore under oath not to enlist again for the king, and they were sent back to London.

Once safely home, parliament appointed the preacher and army chaplain Stephen Marshall, to gather these returning soldiers together, and assure them that the oath was not binding, and to absolve them from it, which he did “with so much confidence and authority, that the Pope himself could not have done it better”.

Whilst the king and his army leadership debated military options at Oatlands Palace, the cavaliers resorted to their habitual behaviour by raiding local villages, ostensibly looking for parliamentary soldiers, but the major objective was to rebuild supplies. First, they plundered where they were stationed. In Walton-on-Thames, the vicar Leonard Cooke complained that he had lost goods worth two hundred pounds , and some of his papers had been burned, whilst Stephen Cheeseman estimated his losses at ninety-six pounds, and Charles Bentley was so incensed at the value of goods that had been stolen from him that he made a formal complaint to the House of Commons who ordered that a search be undertaken for them, presumably once they regained control of the town. After that, the royalists ventured further out. The inhabitants of Byfleet recorded that “when the King’s soldiers were in these parts…our parish was damnified in goods, and victuals at the least the sum of £200”10. In Egham, twenty-two householders valued their combined loss at nearly two thousand pounds11, whilst Robert Marsh from Leatherhead declared that “the King’s forces plundered my house and took away my goods on the 16th day of November 1642”, which was mid-week. Kingston, being occupied by hoards of hungry soldiers, was “miserably plundered”. The list of stolen items was a long one: sheep, cattle, corn, hay and oats, provisions including butter, cheese, wine and beer, coal and timber, household goods, pewter, clothing, bedding and books. In addition, the royalists placed two cannons on Chertsey Bridge in an attempt to hijack boats taking supplies up to London, but they were attacked by a parliamentary detachment from Windsor, who destroyed the bridge.

The general expectation in London during the week following the Battle of Brentford and the stand-off at Turnham Green, was that the royalist army would attempt to march through Surrey towards London, or else to the Kent coast where military supplies from the continent, where Prince Rupert’s relatives were busy buying weaponry, might be waiting. So, parliament ordered additional reinforcements for Southwark and Lambeth on the south side of the Thames, and a bridge of flat-bottomed barges was constructed between Putney and Fulham so that, depending on the enemy movement, the parliamentary army would be able to cross the river without having to return to London. The existence of the bridge of boats was reported in newsbooks, with another of its aims to “prevent the Cavaliers doing of further mischief in Surrey, they having already plundered many little towns near Kingston”.

Upon hearing the news, and still assuming the numerical superiority of his enemy, Charles ordered his army to leave Kingston and march with the artillery to Oatlands, so that by mid-week there were thousands of soldiers in and around Weybridge and Walton-on-Thames. This was not a well-thought-out manoeuvre since it became clear by the end of the week that, even with the provisions being brought back by the “marauding horsemen”, the area could not sustain an army of such a size, and soon soldiers were starting to sell their muskets, and even deserting. Many of the locals had either fled, or were making life as difficult as possible for the invaders, and any remnant of royal support had evaporated. The king’s troops “were then likewise enforced to leave Oatlands, or to be there starved, for all the country people fled, and would bring them in no manner of provision, a penny loaf being at three pence price with them, whereby they were constrained to send out parties of horse by hundreds, and two hundreds at a time to fetch in a bale of straw and their foot soldiers ran away by twenty and forty at a time, saying they were promised to be at the pillaging of London, which failing, they would not stay to be starved”.

From a distance, the Earl of Essex waited with his army to see in which direction the cavaliers — always in front — would head, as his numerical superiority was in keeping his forces together, and he was reluctant to be led hither and thither on a wild goose-chase. But even he was baffled by the cavalier’s activities: some riders headed for Guildford, as if they might head for the Sussex coast; others towards Farnham as if making for Southampton; others were seen galloping towards Kent.

On Friday 18th November 1642, the king made the decision to withdraw from Oatlands, moving first to Bagshot and then to Reading, before heading back to his winter quarters at Oxford, where the whole of his army had returned by the 29th of November. From that point onward, it was evident to King Charles I and Prince Rupert of the Rhine that they would not be able to take London by military means, and so the English Civil War was fought elsewhere, and never returned to Surrey. The inhabitants’ lives, though, had been changed forever, since it would take years for the local economy to recover, partly due to the depredations caused by the cavaliers, but also because of the loss of trade with the royal palaces and great houses of the courtiers, which were confiscated or destroyed during the commonwealth.

Postscript: Prince Rupert of the Rhine 1619-82

The man who slept, fully clothed, at his lodgings in Walton-on-Thames for four nights from Monday 14th to Thursday 17th of November 1642, was a truly extraordinary individual. The son of King Charles I’s elder sister Elizabeth, Prince Rupert was only twenty-three years old when he became commander of the king’s cavaliers in 1642, but he had been a soldier in Germany since the age of fourteen, and was first put in charge of a cavalry regiment at eighteen. He already had a reputation for leading from the front, and was renowned for his death-defying courage and dramatic cavalry charges. In 1644, his capabilities resulted in him being appointed general of the entire royalist army, but he was eventually on the losing side and was banished from England in 1646.

In Europe, he fought for Louis XIV of France against the Spanish, where he was shot in the head but survived. Then, unexpectedly, in 1648 the parliamentary navy mutinied in the king’s favour, and Rupert found himself commander of the English royal navy. He spent the next five years at sea, attempting to improve the royal finances as an ‘official’ pirate targeting English ships in the Mediterranean, North Africa (where he caught malaria) and the Caribbean, initially on behalf of Charles I then, after his execution, of his son in exile Charles II. At the restoration, he became Admiral of the Fleet, a privy councillor, and Constable of Windsor Castle where he maintained rooms that he fitted out like a museum of his military exploits, with vast numbers of weapons and armour.

Prince Rupert was also a businessman, using his travel experiences to invest in the ‘Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa’, whose remit was to look for gold but, inevitably, was involved in some capacity in the slave trade. His next venture was ‘The Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay”, the lands around which were named Rupert’s Land in his honour as the first Governor.12

He had been a prolific source of military inventions during his naval career, and after his seafaring escapades, Prince Rupert turned his attention to scientific matters, becoming a founder member of the Royal Society, and he added a laboratory to his apartments at Windsor to conduct his own experiments. At the same time, he also revealed an artistic talent, producing prints using the ‘mezzotint’ process, which he claimed to have invented, that would replace woodcuts.

In character and personality he was the iconic royal cavalier, or alternatively the image of the dashing, romantic hero may have originated from him. He was six foot four inches tall with a sportsman’s physique (he excelled at tennis), with his long hair worn in ringlets, and in the paintings he posed for was always portrayed as a dandy in masses of loose-fitting silk. He was clever and witty, but could be arrogant, had a quick temper and did not suffer fools gladly. His language was frank and earthy — the diarist, Samuel Pepys, reflecting on sitting on a naval committee with him, noted sniffily that “Prince Rupert doth nothing but swear and laugh a little, with an oath or two, and that’s all he doth.” His personal life was equally anomalous: he never married, but had many affairs and acknowledged two children: a son Dudley Bard and a daughter Ruperta Hughes.

Timeline

| Date | Event |

| August 1642 | King Charles I raised his standard (a declaration of war) in Nottingham. |

| 31st October 1642 | King Charles I and his army left Oxford and marched along the Thames valley towards London. |

| Wednesday 9th November 1642 | Prince Rupert and his cavalry reached Oatlands Palace, intending to attack Kingston to gain control of the bridge. |

| Thursday 10th November 1642 | More parliamentary forces arrived to defend Kingston; Prince Rupert decided not to attack, and withdrew to Egham. |

| Saturday 12th November 1642 | Battle of Brentford, followed by the ransacking of the town by royalist forces |

| Sunday 13th November 1642 | Stand-off at Turnham Green; parliamentary troops left Kingston to support their forces defending the northern route into London. |

| Monday 14th November 1642 | King Charles I left the main part of his army at Kingston, and went to Oatlands Palace for four nights; Prince Rupert and his cavalry were billeted in Walton-on-Thames. |

| Tuesday 15th to Friday 18th November 1642 | The king remained at Oatlands; the cavaliers plundered local villages; the rest of the royalist army left Kingston in mid-week for Weybridge and Walton-on-Thames. |

| Friday 18th November 1642 | Unable to sustain his army, the king left Oatlands for Bagshot, then Reading, |

| 29th November 1642 | King Charles I and his army were back in Oxford, and never succeeded in regaining London. |

Footnotes

- Families of a certain standing were spared, since they could take advantage of the army principle of ‘substitution’, whereby those who were reluctant to join up could hire men without means to take their place. ↩︎

- Old name for Brentford. ↩︎

- The violent seizing of someone’s property. ↩︎

- The main source for many of the events in November 1642 was the publisher Humphrey Blunden whose ‘Passages’ maintained an almost daily account of events, to which he added his own editorial views. However, the survival of such documents is due to the bookseller George Thomason who avidly collected more than 22,000 books, pamphlets, tracts and newsbooks over a twenty year period from 1640 to 1661, which are now held at the British Library. ↩︎

- Almost £800,000 in today’s money. ↩︎

- Robert Devereux was son of the 2nd Earl of Essex who had led a rebellion against Queen Elizabeth I. As a teenager he had married Frances Howard and became embroiled in a huge scandal involving senior members of the royal court. ↩︎

- Gorse. ↩︎

- Prince Rupert’s stay in Walton-on-Thames was recorded in his diary, although he does not mention his place of lodging. It is most likely that it was at the Manor House, since this was the most prominent house in the area. He had, in fact, been briefly at Oatlands Palace a few days earlier on the night of Wednesday 9th November, when an attack on Kingston bridge had first been considered, but later cancelled as it was well-defended. ↩︎

- One of the main parliamentary regiments at Brentford had been raised by Denzil Holles, 1st Baron Holles, who was the second son of Sir John Holles, personal counsellor to Lady Elizabth Hatton in 1617. This regiment was drawn from butchers and dyers apprentices and was equipped with red coats. He is also remembered as one of the Five Members of Parliament whose attempted arrest by Charles I in January 1642 sparked the Civil War. ↩︎

- About £40,000 in today’s money, according to the Bank of England Inflation Calculator. ↩︎

- Equivalent to £400,000, or around £18,000 per household. ↩︎

- Rupert’s Land remained as such until 1870, and covered what are now the Canadian provinces of Manitoba, most of Saskatchewan, southern Alberta, southern Nunavut, and northern parts of Ontario and Quebec. ↩︎

Sources

‘Speciall Passages and Certain Informations’ by Humphrey Blunden; newsbooks for 1642 retrieved from Reporting the English Civil War by Tyger’s Head Books.

Early English Books Online, University of Michigan.

Journals of the House of Commons, Vol II 1642; retrieved from Internet Archive.

Memoirs of Prince Rupert and the Cavaliers by Eliot Warburton; published in London, 1849.

The Civil War in Surrey, 1642 by Henry Elliot Malden; published by the Surrey Archaeological Society in Vol 22, 1909.

The Battle for London by Stephen Porter and Simon Marsh; published by Amberley Publishing in 2010.