Back to Early Modern Elmbridge

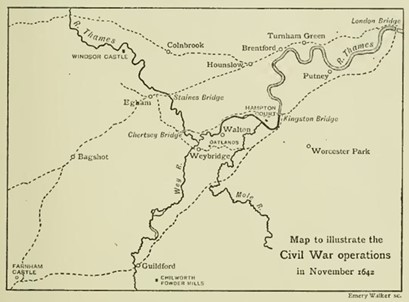

The Seven Day Civil War in Surrey – 12th-19th November 1642: A True Account from Letters, Pamphlets and Newsbooks

Dilemma

The first signs that the war was close at hand came early on the afternoon of Saturday 12th November 1642, when many people heard a series of cracking sounds that continued sporadically over the course of a couple of hours. Then, the next morning, there were reports of distant rumbles, like a giant’s muffled footsteps, followed by a huge explosion. In normal times, those living along the Thames west of London would have blamed the weather and looked for approaching dark clouds, but now they worried that, depending on the outcome of the battle being fought close by, they were soon going to find themselves caught up in the conflict between the king’s army that was marching purposefully towards the capital, and the parliamentarians trying to stop them at any cost.

News had been coming in since late summer from citizens fleeing the capital, that Londoners were preparing for an attack by the royalists, who would approach either north of the river through Middlesex, or south via Kingston Bridge and up through Putney. The ‘trained bands’ of soldiers, who were local militias of reservists called upon in times of need, had been repairing and reinforcing the city walls, and shops and businesses had been closed so that everyone, including women and children, could help by carrying baskets of earth for the ramparts, and gathering materials for the barricades. On the busier thoroughfares, great iron chains had been hung to stop the cavaliers in their tracks, and cannons were put in place beside which the gunners kept a lit flame at the ready.

London had split quickly along partisan lines. At first there were just angry words and accusations, and the adoption of symbols — royal supporters began wearing rose-coloured bands on their hats — but once news that the king had declared war was known, parliament stepped in. The Tower of London and its military resources were seized, and a Committee of Safety was established to take control of the trained bands away from the Lord Mayor and the Aldermen, who by nature and tradition supported the king. A recruitment drive was begun amongst the merchants, craftworkers and apprentices, and a further order was made to raise new troops from the county militias in the Southeast. The challenge was whether all these raw recruits could be assembled, organised and trained before the king’s army arrived.

Then came the clampdown. Anyone suspected of being a royalist ‘malignant’, or refusing to pay the levy that had been introduced to pay for the defences, was stopped and searched in the street to look for weapons, and had their homes raided and horses confiscated. Lookouts scoured the river for boats full of enemy soldiers. Roman Catholics, always thought to harbour royalist sympathies, were given twelve hours to leave London, and were told not to come within twenty miles of the capital again, or risk imprisonment. And so, a steady stream of refugees headed out towards the surrounding counties.

Read more