Leonardo da Vinci and his assistants along with the train of mules carrying his personal belongings, furniture and paintings, one of which is the Mona Lisa which he is still working on, arrive in the Château de Clos-Lucé in the summer of 1516. It has been a long and arduous journey of a thousand miles which has included hurriedly crossing the Alps before the winter set in.

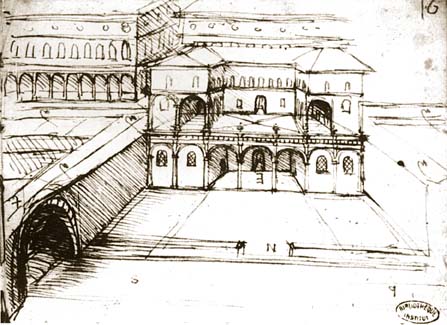

This is the first time in his long life – he is sixty four but with his long grey hair and beard looks much older – that he has left his native Italy. His previous patrons have provided him with work in the various city states of Italy, initially in Florence, then Milan and most recently in Rome where he was lodged in the Belvedere Villa, a recent addition to the Vatican with sweeping views across the city. Here he was employed by Pope Leo X, but found himself struggling to compete with the fame of the younger Michelangelo, riding a wave of admiration following the completion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling after four years of effort.

It was as part of the Pope’s entourage that set out in late 1515 to meet François 1 in Bologna to discuss peace terms, following his anointing as Duke of Milan, that Leonardo met his final patron. In advance of the meeting, the Pope had commissioned an invention from Leonardo that would amuse the young king of France and could be given as a gift. This turned out to be a mechanical lion, two meters high and three meters long and made of wood, that was able to move by way of a single spring and cogs that controlled its motions. It could take a few steps forward, move its tail and sit up on its hind legs. Having done this, a compartment would open up in its chest and a bouquet of lilies would be presented. Lilies were part of the Medici coat of arms, and the Pope had been Giovanni de Medici prior to being anointed as the last ‘non-priest’ to become leader of the Catholic church.

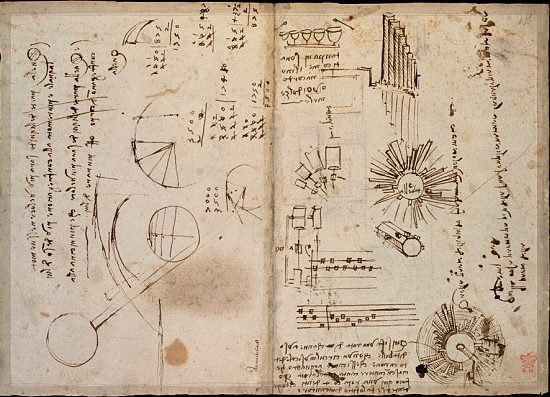

François was already an admirer of Leonardo through his knowledge and admiration for the Italian renaissance, and this must have been the ideal opportunity to offer him security in his old age, as the uncertainties due to the Italian wars continued. Despite his fame, Leonardo is illegitimate and not a rich man by birth so he relies on commissions, many of which he has not completed due to his unstoppable curiosity in everything around him. The title they agree on is “First Painter, Engineer and Architect to the King” and the job comes with a grace and favour home near to the French Court’s summer residence in Amboise, and a decent pension.

Read more