I have written two true stories of the Drakes of Esher – Francis Drake, Esquire and Mrs Joan Drake – during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. These are companion pieces, and together they provide a rare insight into an imperfect marriage during the early modern period, from the perspective of both husband and wife. Whilst they can be read in either order, I wrote Mrs Drake’s story first, and investigated what might have caused her husband’s anger and frustration afterwards.

Both stories have a short version of 3-4 pages (c. 3-4,000 words) which is suitable for publication in local history magazines. However, for those interested in a more in-depth read based on detailed analysis of (and quotes from) the primary sources – court documents from 1605 and a book published in 1647 – plus extensive research of the main people involved, with footnotes of relevant associated facts, a list of sources, and an index, I have made these available both as a ‘flipbook’ and pdf.

Drake vs Drake: The Contested Legacy of a National Hero 1593-1606

In 1593, thirteen-year-old Francis Drake of Esher Place in Surrey is invited to visit his godfather, the celebrated explorer Sir Francis Drake, at his home at Buckland Abbey. He leaves three months later convinced that he will be named his heir and will inherit the estates of the ageing and childless national hero. However, Sir Francis dies off the coast of Panama on his next voyage and makes a hasty codicil to his will, in which he leaves his godson only one small manor for which he has to pay a substantial fee.

This deathbed act leads to years of legal wrangling in which Francis Drake, now in his early twenties, fights for what he believes are his rightful dues against Thomas Drake, Sir Francis’s younger brother and executor, and Jonas Bodenham, a shady character brought up as the son Sir Francis never had to handle his business affairs. There are no holds barred; the only way to win is to drag his godfather’s name through the mud by accusing him of defrauding Queen Elizabeth I twenty years previously. This is the true story of events, based on transcripts of the original documents from the Court of Exchequer in 1605, that revolves around eyewitness accounts of the burning and looting of Spanish colonial settlements in the Caribbean, and the ‘embezzlement and purloining’ of gold coins from a damaged ship of the Spanish Armada whose captain is held to ransom. It is also the story of the young Francis Drake of Esher’s search for identity and what it means to be a man — amidst the piratical machismo of the West Country sailors, and the licentious posturing of the Jacobean court —and his gradual acceptance of his Puritan heritage.

To read full version as Flipbook click here

To download full version as pdf click here

To download short version as pdf click here

The Museum of Melancholy: The Divine Case of Mrs Drake 1585-1625

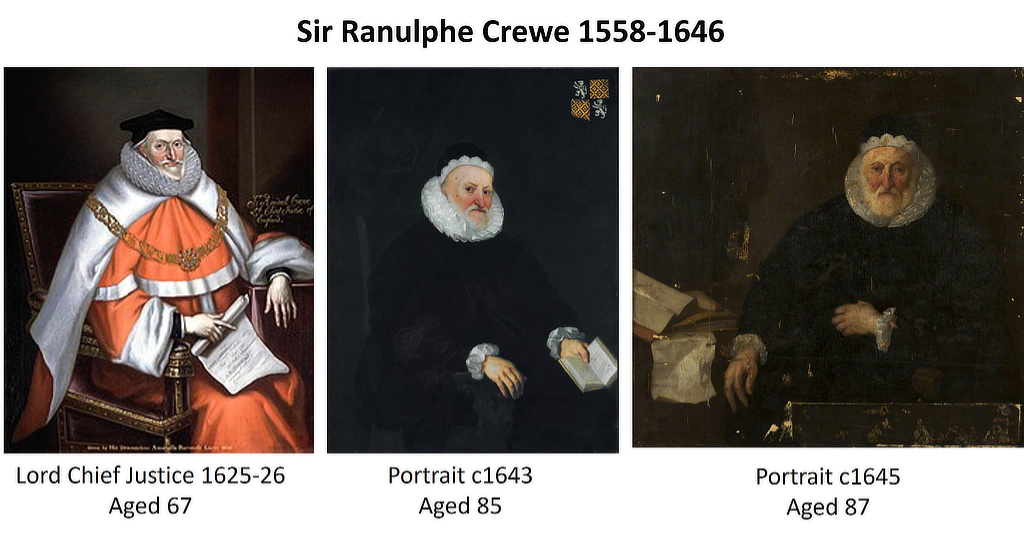

In the early 1600s, Mrs Joan Drake is married to Francis Drake (godson of the great explorer) and lives in Esher Place in Surrey, previously owned by Cardinal Wolsey. They should be leading a charmed life, but she suffers from a deep melancholy that manifests itself in both physical symptoms and a spiritual anxiety. Seeking a cure, Dr John Hart, a Doctor of Divinity, arranges for a series of Puritan preachers to take on her ‘case’ and as the years pass finds himself inexorably drawn into Mrs Drake’s confidence.

Based on the long-forgotten book Hart published in 1647, some twenty years after her death, this is a true account of Mrs Drake’s final years in which, despite the occasional quarrel, she involves him in a secret plan to help her escape — whilst pregnant with her last, ill-fated child — and makes a heartbreaking confession to him on her deathbed. Written as a spiritual guide but concealing a memoir, Hart’s wonderful phrasing and bygone vocabulary form a testament of his devotion, tantalisingly debatable if it was reciprocated or unrequited, but which ultimately proved deadly.

Although the events took place four hundred years ago, the issues are surprisingly contemporary: an intelligent and strong-willed woman struggling with her bodily and mental wellbeing, resolutely combatting the social norms and religious dogma with persistent subversions, and still fervently hoping for a happy ending.

To read full version as Flipbook click here

To download full version as pdf click here

To download short version as pdf click here